Project Report: The Hunger Games in Minecraft

Prepared by: Nic Watson

Concordia University

n.watson@concordia.ca

This report was prepared by Nic Watson, based on research contributed by:

- Saeed Afzal

- Brent Calvelage

- Patrick Grace

- Gersande La Flèche

- Marie-Christine Lavoie

- Tom LeCercle

- Michael Li

- Meghan Overbury

- Nic Watson

This project was conducted at the Technoculture, Art, and Games (TAG) research centre , a division of the Milieux Institute for Arts, Culture, and Technology at Concordia University, Montréal, Canada.

Our research was made possible by the support of the Interactive and Multi-Modal Experience Research Syndicate (IMMERSe) .

In the fall of 2015, under the supervision of Drs. Darren Wershler and Bart Simon, our research team began studying a subgenre of multiplayer Minecraft gameplay called “The Hunger Games.”

This practice uses Minecraft as a platform for competitive deathmatch mini-games which, through thematic trappings, pay homage to Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games novels, and the films based on them. Competitors are referred to as “tributes”, and they are released from “pods” in the centre of a Minecraft-built arena. Often there is a “cornucopia” of food and weapons up for grabs in the start area, as well as equipment kits hidden elsewhere in the arena. There is some kind of boundary—perhaps a glass wall, a dome, or Minecraft’s built-in world border function. Tributes run around in this finite space, hiding, hunting, and hacking at each other, until one victor is left standing.

While earlier examples of the genre had to be played with active moderators and referees, later instances are more refined and make use of server-side scripts for automated game management. This includes, for example, the convention of running an automatic “invincibility timer” that gives players a chance to grab equipment, run away and hide, thus side-stepping the “bloodbath” mechanic seen in the source narrative. Another common convention is to force a fast-paced endgame by teleporting the final few players to a more restricted arena space for a final showdown, or progressively shrink the world border in order to force surviving tributes into an increasingly smaller area.

Minecraft’s rise to prominence and evolution as a game corresponds to the period during which the Hunger Games (HG) novels were adapted into blockbuster films. Overlap between the young-adult audiences for both media properties may have contributed to the establishment of Minecraft Hunger Games (also sometimes called “Hungercraft”) as a genre. Although Minecraft and its mini-games are extremely popular among children, it is crucial to note the role of teen and young adult Minecraft fans as designers, developers, and tastemakers in the mini-game ecosystem.

The Hunger Games is far from the first or only competitive Minecraft mini-game, with other genres including zombie apocalypse maps and one-on-one duels. In Sky Wars , players or teams battle on small islands floating high in the sky, and falling off is a major danger. Spleef is one of the oldest Minecraft mini-games: instead of attacking each other directly, players in an arena attempt to dig the floor out from underneath each other. As the floor becomes sparser over time, it gets harder to move around and avoid falling into the pit below. Minecraft-based variations on the multiplayer deathmatch genre are not inspired by the Hunger Games alone: in addition to following numerous other precedents of arena-based mini-games in Minecraft worlds, they draw on the rich ludic traditions of games such as Quake and Unreal Tournament .

Because Minecraft maps are naturally expansive and varied, a mini-game must usually take place in a

bounded space designed (and often narratively themed) specifically for that purpose—that is, an arena. Simpler, smaller

arenas for games like spleef are sometimes found embedded in larger, persistent multiplayer worlds that are used for general

play, with players choosing to hold special mini-game events on occasion. Such events are circumscribed in space and time,

set apart from the rest of the activity on the Minecraft server. Larger and more complex arenas are more likely to have

dedicated servers used only for that purpose, especially since there is often a need for server-side plugins (mods) to tweak

Minecraft’s rules in order to enforce and facilitate rules and actions specific to the mini-game.

Although the “default” theme for a Hunger Games map is a large forested space, mimicking that seen in the films, many

other themes have proved popular, from volcanoes and urban cityscapes to a re-creation of The Simpsons’

Springfield.

The project consisted of two phases.

First, we were tasked with mapping out the procedural rhetoric of Minecraft Hunger Games, identifying its key features as well as its major variants. Which characteristics are essential for a mini-game to be considered Hunger Games? We were also on the lookout for emergent play patterns – the strategies and behaviours exhibited by players as they navigate the procedural play space, aspects of the game that are not obvious from simply reading the rules. For instance, do players form secret alliances early on in the game, and then betray each other? How do these dramas play out? How do players signal their intentions to cooperate with one another? Do most people try to fight or do they run and hide? Do people play with friends, family, or strangers, and how might those relationships affect their in-game interactions?

Our second task was experimentation: what happens if we change up some of the essential characteristics of Minecraft Hunger Games that we identified? How much can we change before we get something that can no longer reasonably be called Hunger Games? Can we introduce other game mechanics, like mandatory cooperation, progression (through a series of goals or levels), puzzles, and boss fights?

In particular, we had an eye towards creating “critical mods” of the Hunger Games concept to be tested by sociology students in Professor Bart Simon’s introductory sociology course. We aimed to see if we could adapt the Hunger Games to enable students to interrogate a range of questions with sociological themes, like class structure or resource scarcity. To what extent would the genre enable this kind of use, while still remaining Hunger Games at its core? What sort of scripts or suggestions would we need to supply? Alternatively, would the procedural backdrop alone be sufficient to produce HG-like play behaviours, absent any suggestions or instructions?

These manipulations serve to push against the question of genre. What does it mean to call something Hunger Games anyway? We hoped, through our experimentation, to create boundary objects (Star and Griesemer, 1989) – things that are somewhere between being Hunger Games and not-Hunger Games depending on who is encountering them and how. Such games could serve as tools for thinking about the significance of genre, for ourselves and our players.

Most of the goals of the project were never completed due to lack of time and participants moving on to other projects. This report provides our partial results and preliminary findings.

For the first phase of the project, a team of nine undergraduate students participated in Hunger Games sessions on Minecraft server networks like MC-Central and MinePlex. Additionally, the students selected popular YouTube “Let’s Play” for review. Students conducted open coding (Strauss, 1987) to identify the salient characteristics of Hunger Games instances.

We developed four categories of analysis:

- Common elements: these are seen in all, or almost all, Hunger Games scenarios. A mini-game lacking these components would be difficult to classify as Hunger Games.

- Variables: these characteristics are found in some instances of Hunger Games, but not in others. They nevertheless act as significant inflections on the game mechanics: players will want to know which variable characteristics are present in the match they are about to play, so that they can adapt their actions accordingly.

- Themes: this heading catalogues visual aesthetic motifs and transmedia references in Hunger Games arenas.

- Variants: different from variables, this category aims to classify recognizable, common packagings of game mechanics into types of Hunger Games matches.

After gathering data on existing implementations of the Hunger Games, we turned to the design of new prototypes, intended to engage with the ideas and questions that came up during our initial exploration. As individuals or in pairs, we developed and pitched ideas for Hunger Games arenas that could later be tested with Dr. Simon’s sociology students. Designs began as pencil-and-paper sketches, which were then built in Minecraft, either using the in-game Creative Mode or with third-party editors like MCEdit. Some team members built their prototypes on our persistent, shared Minecraft server space, while others worked independently in locally-stored, single-player worlds.

Our intention was to select one or two of the prototypes, demonstrating ideas that we thought were particularly worthy of further investigation, and further develop them as a group. We would then test these polished prototypes with our “tributes”. However, as time ran short and several members of our team became too busy with other late-semester duties, we were unable to follow through on the original plan. Instead, we selected the most highly developed prototype, created by Brent Calvelage. This map, with which Brent had already conducted multiple smaller playtests, became the focal point of our three-hour playtesting session with about a dozen of Dr. Simon’s students in December, 2015.

Throughout the project, the students also made blog posts on topics of their choice relating to the project in some way. These were originally intended to be “weeknotes” – brief, weekly accounts from each participant of what they had accomplished that week, what they were working on, and what research questions they were pondering. In practice, the student posts ended up being less frequent but more in-depth analyses of specific questions of interest, such as the stability of the Hunger Games label as a genre, the presence of unwritten rules and norms, and mismatches between the Hunger Games source narrative and deathmatch game mechanics. Summaries of these articles are included in this report, in their relevant sections according to subject. (Some posts may appear in more than one section of this report.) The full posts can be found at http://www.amplab.ca/tag/mchg/

As we searched for public Hunger Games servers and YouTube videos, we realized very quickly that “Hunger Games” was not a stable genre category, but more like a fuzzy Web 2.0-style tag that could be attached to certain types of Minecraft mini-games to give them a different cultural valence. Indeed, we observed non-Hungercraft servers that made no mention of, or claim to offer, Hunger Games except in the casual use of the #hungergames tag in advertisements and promotional database listings.

Even the most “pure” of Hunger Games matches selectively implements some aspects of the source narrative while ignoring others. In these instances, true to the film depictions, players start in a central location, with a “cornucopia” of loot and equipment (meant to encourage a “bloodbath” of kills in the first few seconds). Thematic trappings that pay homage to the books and films may also be present—text instructions that refer to competitors as “tributes”, entry tubes or elevators, and a “cannon” that detonates TNT in order to signal the death of a tribute. PvE (player versus environment) mechanics are downplayed in Hungercraft, with hostile mobs often absent. This is a departure from the books/films in which the need to find food and clean water, and to avoid hostile wildlife, are key factors in the drama.

Hungercraft variants have no problem altering or abandoning key game mechanics while maintaining the claim to be “Hunger Games.” We observed invincibility timers as common features—the server disables PvP (player versus player) combat for a brief period (30 seconds to a minute) at the outset, giving players time to grab equipment, run away, and hide. While these timers are common in multiplayer PvP deathmatch games generally, and are intended to make gameplay more interesting, in this case they sidestep the bloodbath mechanic, which is an intentional feature of the Hunger Games premise.

We also noted a proliferation of themes for Hunger Games maps, going well beyond the domed wilderness spaces seen in the films. One arena recreates the town of Springfield from The Simpsons , while another aesthetically positions players as miniscule people in a gigantic version of the 4J Studios employee lounge (4J develops the console versions of Minecraft). The expansive variety of fan-built arenas is not surprising in itself—similar variation can be seen in fan-made maps for a variety of other PvP games, such as Unreal Tournament . However, it suggests the need to understand Hunger Games as a particular flavour of Minecraft PvP deathmatch, one that owes its current form more to precedents and conventions from PvP deathmatch practices in general, and less to the Hunger Games narrative.

Our team wrote several posts addressing the question of whether there was a Hunger Games “genre”, and the use of “Hunger Games” as a tag:

-

Remaking/demaking the essential elements of Hunger

Games by Nic Watson

- Nic suggests that the genre problem becomes particularly apparent if we imagine trying to re-create the essential elements of Hungercraft in another game engine. Game engines are not neutral platforms: their affordances inflect how play is understood by players. The notion of Hunger Games might work in Minecraft since it is not primarily an arena deathmatch engine, making Hungercraft easily distinguishable from “normal” Minecraft play. If we remade the Hunger Games for Unreal Tournament , they would be much more difficult to differentiate from all the other forms of Unreal Tournament .

-

The paradoxical nature of genre by Patrick Grace

- Patrick argues for understanding genre as a fractal phenomenon: “Study into any genre tends to reveal further layers of genre underneath, where the second layer resembles the first. Intensified study may reveal more information, but it increases distortion and is not necessarily useful.” The “genre” of a Minecraft minigame may be tied as much (if not more) to how we thematically represent it as it is to underlying game mechanics.

-

The #HungerGames

function by Marie-Christine Lavoie

- Marie reviews several uses of the “Hunger Games” tag in server advertisements, noting that it is often applied to servers that, upon further inspection, have nothing to do with the Hunger Games. This undermines the notion that there is an identifiable “Hunger Games” subgenre. Marie proposes instead that the tag leverages what Foucault calls the “author function” to infuse Minecraft deathmatch servers with “credibility” as transmedia storytelling. The audience’s familiarity with HG can, in Jenkins’ words, allow transmedia authors to “skip over transitional or expository sequences, throwing us directly into the heart of the action” (Jenkins, 2006, p. 120). Ultimately, the promise of a “fan generated transmedia narrative that allows players to interact with aspects of the media they normally would not have access to” is not borne out, as Hungercraft servers “reduce the narrative to a single moment: the arena battles.”

-

Agit histrionem – Level design’s

effect on play by Brent Calvelage

- Brent notes that maps with a lot of environmental hazards are less likely to bill themselves as true “Hunger Games” and more likely to be tagged as “Hardcore survival with PvP”, despite the fact that the existence of a hostile environment is closer to the film/book version of the Hunger Games than the inert Minecraft arenas that are usually tagged as HG.

Although our interrogations of the genre issue yielded no satisfactory answers, the questions themselves were fruitful. We realized that our investigations were ensnared in an ambiguity regarding what sort of genre are/were we looking for: there were (at least) three possibilities.

On the one hand, we could ask if there is a Hunger Games game genre organized around the mechanics of play —- the type of genre we invoke through terms like “first person shooter” and “real time strategy.” In this case, we would attend to indications that a consistent set of game mechanics has (or has not) emerged around the Hungercraft label within the broader Minecraft minigaming community. Alternatively, we might ask if we can find within Minecraft minigaming a narrative genre , in the same sense as “dystopian science fiction” or “perilous survival adventure.” Here, we would ask to what extent the minigames recreate or depart from the narratives and themes of the source text.

The third approach requires that we recognize that tropes from the source narrative are not limited to becoming visual themes, allusions, and window dressing in the game version, but can actually become game mechanics in their own right. In the Hunger Games films, the background political struggle constantly insinuates itself into the tributes’ struggle for survival. We can imagine game mechanics based less around the tributes killing each other and more on their resistance to the forces that exploit them: for instance, there could be hidden opportunities to escape or tamper with the functioning of the arena itself. If Hungercraft were to make game mechanics out of these other aspects of the source narrative, beyond the deadly arena competition, then a strong case could be made for treating it as a distinct genre, offering a fundamentally different experience from other Minecraft-based deathmatch games.

As some of us were, at the outset, more familiar with the Hunger Games film narrative than we were with the Minecraft minigame, we were naturally attentive to how aspects of the narrative were, or were not, embedded in-game. We attempted to play out versions of the cinematic drama 0n public Hunger Games servers, and to design for them in our prototypes.

We quickly found that popular large-scale HG implementations resisted all but the most superficial and generalizable attempts to play out narratives and strategies similar to those adopted by characters in the film. In one telling example, Brent tried to enact the survival strategy favoured by the film character Peeta Mellark, in which he skillfully conceals himself in order to avoid violent encounters with competitors for several days. Brent echoed this behaviour by avoiding direct combat whenever possible, fleeing from confrontation and hiding in remote corners of the map. He soon discovered that this behaviour was frowned upon, since it tends to drag out the game and forces competitors who prefer fast-paced fights into a tedious hunting-and-chasing endgame. As a result, Brent reports, “banhammers were liberally applied to me.”

Brent found that larger, more prominent HG servers were set up to privilege fast gameplay and high turnover. Only on smaller, more eclectic servers, were hiding mechanics considered a normal part of the game.

- See also:

- Spoilsports, cheats, and other undesirables by Brent Calvelage

Meghan notes that alliances and teamwork are important parts of the HG source narrative: tributes band together early on for survival, though these alliances inevitably break down. Importantly, the protagonist Katniss sticks with her team to the end, on both occasions when she finds herself in the arena, always finding some way to subvert the forced betrayal mechanic that the game rules try to force upon her.

According to Meghan, alliances are virtually absent from Hungercraft games: some players (newbies, perhaps) attempt to forge temporary alliances at the beginning of a tournament, but these requests are often ignored.

Meghan finds the lack of teamwork particularly intriguing given that Minecraft generally tends to encourage collaboration, and teamwork is observed on Maze Runner and Harry Potter themed servers. She suggests that the affordances of the chat system –- the need to stop running or fighting in order to type a message, and the added difficulty of restricting a message to specific recipients –- may help explain why Hungercraft tributes tend to play as lone wolves.

- See also:

- A case for teamwork by Meghan Overbury

In the first Hunger Games film, a trainer admonishes the tributes to not get too hung up on the combat aspect of the games, as most of them will die due to dehydration or environmental hazards. Naturally, this information is quickly forgotten as the film goes on to kill the majority of tributes in Hollywood-suitable cinematic fighting sequences or shocking cold-blooded executions. Nevertheless, the hostile environment is supposed to play a key role in the Hunger Games drama, which implies that a game based on the narrative should contain a strong player-versus-environment (PvE) element.

On the contrary, the drama of Hungercraft is almost entirely focused on the player-versus-player (PvP) conflict. Arena designs usually keep environmental hazards to a minimum and funnel players into deadly confrontations with each other. Meghan suggests that the direct, violent triumph over other players is part of the payoff, and is more rewarding than merely outlasting them in a fight against the environment: “it’s a lot more satisfying to win by killing your opponents rather than just have them all die off because they can’t defend themselves against the elements.” Brent made a similar observation in his own playtests of a hostile design prototype arena called “Hell.” He noted that players who were about to die in combat would sometimes jump off a cliff or into a lava pool, just to spite their pursuers by robbing them of the final blow. Furthermore, many tributes died due to tiny missteps, making the winners feel “cheated” because their victories was less about their own abilities than about luck.

On the contrary, the drama of Hungercraft is almost entirely focused on the player-versus-player (PvP) conflict. Arena designs usually keep environmental hazards to a minimum and funnel players into deadly confrontations with each other. Meghan suggests that the direct, violent triumph over other players is part of the payoff, and is more rewarding than merely outlasting them in a fight against the environment: “it’s a lot more satisfying to win by killing your opponents rather than just have them all die off because they can’t defend themselves against the elements.” Brent made a similar observation in his own playtests of a hostile design prototype arena called “Hell.” He noted that players who were about to die in combat would sometimes jump off a cliff or into a lava pool, just to spite their pursuers by robbing them of the final blow. Furthermore, many tributes died due to tiny missteps, making the winners feel “cheated” because their victories was less about their own abilities than about luck.

The following blog posts further discuss PvE elements (or their absence):

- The nature of conflict; a conflict of nature by Saeed Afzal

- When arenas attack by Meghan Overbury

- Agit histrionem – Level design’s effect on play by by Brent Calvelage

- Ravenous recreation by Brent Calvelage

The Hunger Games background story is, of course, the most conspicuously absent narrative feature in Minecraft adaptations. There is no political struggle underpinning the game, no sense of injustice, no juxtaposition of the upper class’s refined manners with their bloodthirsty barbarism, no sense of the countless murders that take place outside of the games. Most importantly, the stakes for the Hungercraft player are nothing like those for the tributes of the source narrative. There is no sense of being unceremoniously accosted from your former life, no promise of being lifted out of poverty for the victor, and no visceral, ever-present, terrorizing mortal danger. Nor is this explained by the fact that Hungercraft is merely a video game: many games succeed in getting players emotionally invested in the protagonist's wellbeing, but Hungercraft characters have no background, no existence beyond the bounds of the arena, nothing to gain and nothing to lose. This helps to explain why players are content to jump into lava to spite their attackers, and why they may prefer risky combat over running and hiding. The narrative backdrop that so richly informs the arena activity in the books and movies is, in Michael Li’s words, “lost in translation.”

In their blog post, Crafting autonomy in Minecraft , Gersande argues that the intrinsic motivation for all players in Hungercraft is simply to beat your opponents. This differs from the various motivations that inform the actions of characters in the books and movies. Thus, the Minecraft version fails to dramatize the tension between autonomy and socialization that Gersande identifies in the source narrative – “the kind where one’s allies are also explicitly one’s adversaries.” At the same time, it also elides the self-sufficiency narrative of standard vanilla Minecraft play. Gersande wonders how the physical design of the arena can inform how players find motivation for their in-game actions.

Taking a different angle, Michael suggests that explicitly invoking a narrative layer may inflect player motivations in new ways. Perhaps they will play differently if they are nudged towards roleplaying a character who has to grapple with the terror of the scenario. Michael advocates creating a prototype that provides players with a backstory lens through which to interpret their situation.

Saeed offers our final word on narrative adaptation. He states that, broadly speaking, Hungercraft implementations are not concerned with converting narrative elements into game mechanics. Instead, Hungercraft is a “well oiled machine” of efficient, repetitive deathmatch games with thematic trappings from the Hunger Games sprinkled over everything (giant Mockingjay pins, the practice of referring to players as “tributes”, and other fairly inconsequential gimmicks. While the film/book Games are a monumental affair, Saeed writes:

In Minecraft, we get the fast food version of that: it’s quick, it requires minimal effort, it involves as little human intervention as possible, it offers only fleeting satisfaction, it ends just as you’re starting to enjoy it – but is always there, open for you 24 hours a day, to indulge in – and you feel just a little greasy afterwards.

After several weeks of sampling Minecraft Hunger Games offerings online, in preparation for our prototyping phase, we compiled a list of game mechanics that we found to be either ubiquitous or intriguing. This list is not exhaustive since we left it somewhat unfinished in order to focus on having prototypes ready for playtesting.

| Feature or convention | Rarity |

|---|---|

|

Self-sacrifice Some players can (or must) voluntarily sacrifice themselves in order for others to win – either because of the form of the map itself, or as emergent cooperation between allies to best an opponent. |

Rare |

|

Dungeons and ruins The arena features ruins or small explorable spaces, which may contain traps or treasure, or provide thematic hiding spots. |

Common |

|

Underwater arena A large portion of the map is under water. Players must periodically visit pockets of air in order to survive. The environment itself is significantly more deadly than in the average arena. |

Rare |

|

Rising lava or sea Players are forced to higher ground by rising water or lava. The space available for play gets smaller, which forces competitors into confrontations with each other. |

Rare |

|

Status effects (e.g. potions) Arena-based triggers or drinkable potions give players temporary buffs. |

Semi-rare |

|

Starvation Players need to find or make food in order to avoid starving to death. Food – and competition for food – becomes a significant aspect of gameplay. Such a game needs to last long enough for starvation to have chance to kick in. |

Rare |

|

Desolate wasteland The arena is naturally war-torn from repeated play. The scars or explosions and digging are left over from previous games. The map is not reset between matches. |

Common |

|

Respawning chests Useful equipment kits are found in chests around the map. The equipment is automatically regenerated on a timer. |

Common |

|

Artillery/airstrikes Players can attack each other with explosive bombardments from afar, or explosive bombardments act as a constant environmental hazard. This usually requires mods. |

Rare |

|

Combat with lava buckets Instead of hitting each other directly, players must try to slay each other indirectly, by dumping hot lava buckets on each other. |

Semi-rare |

|

Incentive – scoreboard Every player can see a display of who is still alive, and how many kills each player has registered. |

Common |

|

Incentive – kill-count chests Chests containing rare equipment unlock for players who have killed a certain number of foes. |

Semi-rare |

|

Reward – keys Reward kits include keys that open up new areas. |

Rare |

|

Reward – food Reward kits include food items that the player can use to regenerate health and stave off starvation. |

Semi-rare |

|

Reward – building materials or trap materials Reward kits include materials that a player can use to construct protective shelter or build deadly traps for others |

Semi-rare |

|

Reward – Ender Pearls / ease of movement Reward kits contain Ender Pearls, which are throwable items that instantly teleport the thrower to the location where the pearl lands. This can be used for fast movement across the map, and especially to escape from dangerous situations. |

Semi-rare |

Brent’s article,

Agit histrionem – Level design’s effect on play , identifies three variables of level design that shape how HG matches play out: size, mechanical complexity, and deadliness of the environment. In brief, small maps provide fast-paced gameplay and are often preferred for that reason, given that matches on large maps can take a long time to conclude. However, because of their simplicity, small maps have less replay value because they are easy to memorize. Deadly maps are more likely to result in players feeling “cheated” because other competitors died due to environmental hazards.Our original plan was to start by collaboratively designing and testing a conventional Hunger Games map, according to the same conventions we observed on existing servers. This would allow us to achieve the following:

- Determine the strengths and expertise of each team member

- Establish a workflow for integrating each participant's contributions into a single cohesive map prototype

- Introduce our target playtesters -- Concordia sociology students rather than habitual Hungercraft players -- to the genre

- Conduct a "dry run" playtest in which we get a baseline for our playtesters' behaviour, for later comparison when we implement and test experimental arenas

For the next step, individually or in pairs, each member of the team was to produce a design document or proof-of-concept for an experimental Hunger Games map. These proposals were to choose a particular mechanic or variable that we had previously identified, describe how it was to be “tampered with” in the experimental prototype, speculate on potential playtest outcomes, and explain what could be learned from such outcomes regarding either transmedia storytelling or sociological experimentation in Minecraft.

The team would collectively choose a favourite (or two thematically-related favourites) among the proposed candidates, for development into a full prototype.

With participants having limited hours available to devote to this project, and our end-of-semester playtesting deadline fast approaching, we skipped the initial conventional map design, and proceeded straight to the experimental proposals.

Our ideas fell into four broad categories:

- Re-introducing mechanics from the source narrative, such as conspicuous spectatorship, hunger and starvation, sponsor gifts, and active interference by the game masters.

- Manipulating player behaviour through the physical design of the arena, primarily by thematically signaling and/or actually implementing a tame or hostile environment.

- Creating new thematic frames or providing instructions to players that seemed to be at odds with Hungercraft conventions or with arena designs (e.g. suggesting to players that the victory condition was simply to survive, without stating that other players had to be killed).

- Forcing, or creating the conditions for, collaborative action that appears to go against the stated premise of Hungercraft (e.g. providing puzzles that require multiple players to solve, or introducing a collective action problem such as a rising sea level).

Some of our proposals are documented in blog posts, which are highlighted below.

-

Breaking the mold by Michael Li

- In this post, Michael advocates for designs that go against the grain of existing Hungercraft convention in noticeable ways. One proposal involves blending Hunger Games with Complete The Monument, another popular Minecraft mini-game that is typically played collaboratively, with puzzle or PvE elements. A second proposal involves mechanical puzzles that provide material rewards, but that are wired in such a way that at least two players are needed to solve them (Category 4, above). Finally, Michael suggests a bowfighting-on-a-mountain scenario in which no other weapons are provided, as a subversion of the typical hack-and-slash mechanic as well as an homage to Katniss Everdeen’s weapon of choice (Category 1, above).

-

Place for a

“real” Hunger Games server? by Marie-Christine Lavoie

- Marie advocates for a more “authentic” recreation of the Hunger Games experience in Minecraft (Category 1). She

writes:

What seems to be the crucial element in the realization of a “Hunger Games” server is the player-versus-player arena. Why do I say this is crucial? Every #Hungergames servers we have tried has revolved around players fighting other players in order to survive and “win”. However, that appears to be the only thing that is like “Hunger Games”. I believe this is boring and is just an excuse to call everything #Hungergames when in fact, it is only PVP.

- Marie’s design idea calls for the inclusion of “gamemakers”, individuals with Creative Mode abilities who can modify the arena, drop items for tributes, and otherwise intervene during the game in order to funnel players into more exciting and dramatic situations, as the gamemakers do in the source narrative.

- She further suggests including an aspect of the tribute selection process, a key moment in the lives of HG film characters which induces either intense excitement or sickening anxiety, depending on one’s District of residence. In Marie’s scenario, each player would be assigned randomly to one of the twelve Districts, and players would wait in a District-specific lobby to be randomly selected as their District’s representative. In a restaging of one of the most dramatic moments from the film, a tribute could “volunteer” to take another’s place.

- Finally, Marie points to Potterworld as an example of a Minecraft server that recreated the fully-featured social world of Harry Potter’s Hogwarts School for Wizardry and Witchcraft, complete with professors, students, prefects, and storywriters. She wonders about the feasibility of a server that similarly recreated the broader social milieu of Panem, with the “games” themselves informed by a backdrop of class roles and political struggle.

- Marie advocates for a more “authentic” recreation of the Hunger Games experience in Minecraft (Category 1). She

writes:

-

Hunger Games design #1 by

Marie-Christine Lavoie

- This piece describes a design mock-up built by Marie and Saeed on our research centre’s dedicated Minecraft server. The design was intended to test the feasibility of adding an observation layer above the arena from which gamemakers could observe the action (as described in Marie’s post above). The gamemaker’s platform would have switches for controlling mechanisms below. Additionally, hazards such as monsters and lava could be dropped from above in order to manipulate players.

-

Cornucopia from Marie

and Saeed's prototype. Screenshot by Marie-Christine Lavoie.

Cornucopia from Marie

and Saeed's prototype. Screenshot by Marie-Christine Lavoie.

-

Crafting Dynamics by Tom

LeCercle

- Tom’s design, a network of platforms and crisscrossed staircases, aims to foreground bowfighting (Katniss’s combat style of choice), reducing the role of the hack-and-slash combat typically seen in Hungercraft (Category 1). This arena became the prototype for the “citadel” found in the centre of the Icarus map design, described in Section VIII below.

-

Tom's bowfighting

arena / Icarus citadel precursor. Screenshot by Tom LeCercle.

Tom's bowfighting

arena / Icarus citadel precursor. Screenshot by Tom LeCercle.

-

Ravenous Recreation by Brent

Calvelage

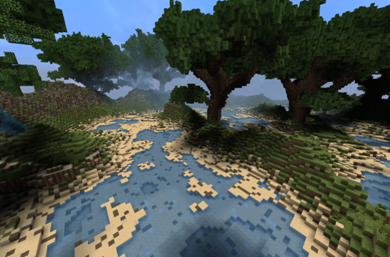

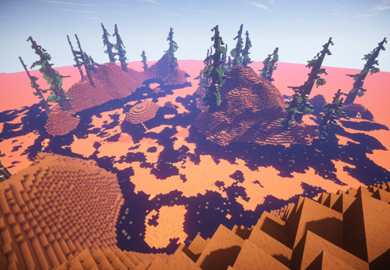

- In order to further his investigations into how physical level design gives rise to some play behaviours and not others, Brent designed two arenas: the lush Eden, with green grass, peaceful ponds, large trees, plenty of food and lots of places to hide; and the aptly-named “Hell” of shallow sands, ashen wastes, and lakes of fire. Brent’s findings are briefly summarized here, while the article itself provides a more detailed account.

- In Brent’s playtests with his friends, the maps yielded very different tactics, play styles, and match durations. Eden exhibited a diversity of play styles, and hiding was a common strategy: “Players realised hidden farms were the easiest way to win rather quickly and gameplay became a strange version of cat and mouse, with the mice sometimes becoming cats out of boredom, and cats becoming mice out of necessity.” Hiding and farming food were nearly impossible in Hell, and direct player combat was common, though many players died by accidentally stepping into lava. In both cases, the “end game” (the phase at which only a small number of players remains) dragged out for a long time, because it became easier for the smaller number of players to avoid each other.

- Brent concludes that “simple Minecraft worlds and the variation of scarcity of certain materials on its own is enough to create a Hunger Games environment, but which ones were artificially limited changed player behaviour in a myriad of ways.”

-

Brent's

'Eden'. Screenshot by Brent Calvelage.

Brent's

'Eden'. Screenshot by Brent Calvelage.

-

Brent's

'Hell'. Screenshot by Brent Calvelage.

Brent's

'Hell'. Screenshot by Brent Calvelage.

After the playtest, Brent and Tom further collaborated to produce a final prototype combining elements of two previous designs. This arena, called Icarus, is further described in Section VIII, below.

In December 2015, we conducted a three-hour playtest with students from Professor Bart Simon’s sociology class, SOCI 498, “Play, Games, and Technology.” Roughly half of the students had some prior experience with Minecraft. The playtest was held at the Technoculture, Art, and Games research centre at Concordia University. We used a combination of students’ personal laptops and lab-provided desktop computers. Due to limited equipment and table space, three testers had to be located in a separate room across the hall, which made it difficult to observe them, and necessitated that we cross the hall several times in order to deliver new instructions or help with troubleshooting.

Testers played three different modes of Minecraft Hunger Games: fast, public matches on MC-Central; a locally-hosted “traditional” HG map for our testers only; and Brent’s experimental “Eden” prototype.

First, as we were assisting some students in getting set up, those who were ready logged in to MC Central, a massively popular multiplayer server network (Test #1). There, they played through several games (each 5-15 minutes each) of the same sort of Hunger Games scenarios that we had previously investigated – the kind that Saeed compared to fast food. These servers use Bukkit plugins to enforce rules, enact arena resets, and provide a seamlessly automated experience. MC-Central’s arenas tend to be creatively themed and visually compelling, but the game’s namesake activities—mining and crafting—are not possible. One playtester, Alex Kozina, later wrote that the appeal of these games may have less to do with Minecraft’s much-celebrated affordances for bricolage, and more to do with the voxel aesthetic that it popularized.

Next, the testers all played on a locally-hosted, highly conventional Hunger Games map not of our own design, that we downloaded from PlanetMinecraft.com (Test #2). This modest-sized arena was grassy and wooded, with a few derelict cottages dotted about, and a central circle of piston mechanisms to deploy tributes into the arena – a recreation of the entry elevators from the fiction. Tributes played in Adventure mode, meaning that, like on MC Central servers, they were free to move around and attack one another, but could not break blocks or craft items. When killed, players were to reappear in a respawn area, where a Command Block mechanism would trigger to put them in Spectator Mode. This would allow them to fly around the map as phantoms, able to see everything but unable to affect anything.

For the most part, students either chased each other around with swords, hacking and slashing, or ran and hid. The pattern of tribute deaths was consistent with what we had seen in our prior research: several deaths at the beginning, followed by a long tail of periodic defeats, with the occasional “cluster” of slayings (reflecting, for instance, two players dying in a three-way fight).

The biggest takeaway from this roughly 30-45 minute ordeal related to the procedural fragility of the technical systems enabling HG play. Since Minecraft was not originally designed for competitive arena games, but rather for open-ended building, arena games need to use a combination of command blocks, redstone machines, and active management by a game master in order to make sure that the rules and boundaries are properly observed. As noted, the “well oiled machines” of MC-Central and MinePlex make heavy use of server-side mods to produce the exact behaviours intended by their game designers. Furthermore, many of these mods are not third-party creations selected from online databases, but are actually custom-built by server operators and tailored to their specific needs, according to one major server network operator (personal correspondence).

Our Test #2 was held in a vanilla (unmodded) Minecraft software environment, relying only on the mechanisms that the map designer had built in. For reasons that are not entirely clear, but perhaps due to designer error or bugs arising from the fact that the map was made in an earlier version of Minecraft, these mechanisms failed. Our own tampering may also have contributed: some of the mechanisms were apparently designed to trigger only once, so when I tested them out in-game before inviting others to the map, I unwittingly sabotaged them.

The latter explanation likely reveals why some of the entry pistons failed, leaving a few players trapped in small holes at the beginning of the game. These pistons are intended to mirror the operations of the entry elevators in the source narrative, which lift all tributes up into the arena and release them all simultaneously. In this Minecraft map’s implementation, each player stands atop an upward-facing piston, in a one-block-deep hole, with an extra one-block surrounding wall made of glass. The player can look around, but is unable to jump out of the hole until they receive an upward boost from the piston. A game master uses a switch to activate all pistons simultaneously. Since players are in Adventure mode, they are also unable to break through the glass. This prevents anyone from getting an unfair head start, but also means that players can’t escape in the event of a piston malfunction. Since some of the pistons did just that, I ended up having to run around the ring in Creative mode, breaking glass in order to release trapped tributes.

Another malfunction occurred in the respawn area. As described above, dead players should have been automatically put into Spectator mode, but the trigger mechanism failed, leaving them stranded, frustrated, and confused as they crowded together in a tiny, inescapable “spawn jail” and, in some cases, continued punching each other to death. Testers unfamiliar with the Minecraft HG genre in particular had no way of knowing that their new situation was the result of a technical glitch, and some appear to have proceeded as if it was simply a second phase of gameplay, with the same general goals (i.e. slaughter everyone). Others disconnected and reconnected in hopes of resetting themselves, but unlike MC-Central’s games, a normal Minecraft server maintains a persistent memory of player state, so reconnecting players simply found themselves back in the Limbo they had just left.

The frustration and bewilderment was palpable, both in the physical room and in the mess of jumping/punching/dying avatars in the spawn jail. Typing furiously, I did my best to put each dead player, one by one, into Spectator mode. This was complicated by the difficulty of reading individual player nametags when so many players were clustered together in one spot, and by the fact that players kept attempting to reconnect: my typed command would fail if the target player logged off just before I finished typing it. Having to deal with the respawn disaster meant that I was unable to watch the ongoing competition between the tributes that had not died yet.

Eventually, one victor was left standing, and after a brief congratulations, I shut down the server and explained that we were now going to try an experimental map that a member of our own team designed.

Brent had been preparing a new prototype, based on the feedback he received on his own Eden and Hell designs. In his postmortem report, The Sum of its Parts: The Hunger Games in Minecraft, he describes this design as follows:

It would be of medium size, to allow hiding, with hidden chests containing some loot to encourage exploration, food would be scarce, to encourage tactical long-term thought, and lastly, it would be weapon heavy, to make fighting appealing. In the final days of mapmaking, I started focusing on a spawn area and thinking of if mobs should be immediately enabled and what starting equipment players should have. I considered using treasure chest randomizers and a compass to track other players down, but the idea was stashed temporarily in favour of having a map that was accessible to vanilla players.

Unfortunately, this brief description is all that survives of this prototype. Two days before the play-test, the map files became unusable due to data corruption. This is the perennial risk of using experimental, third-party programs like MCEdit to design Minecraft maps. Although MCEdit is a powerful tool that provides map design affordances not available through the in-game Creative Mode, bugs in the program can cause unpredictable and destructive glitches. As a fallback, we tested players on Brent’s earlier Eden prototype instead. However, since he had not originally intended it to be used for this session, it contained some hidden surprises as well.

My hope for this Eden test was to create ambiguous motivations for players, providing them with explicit and implicit goals and suggestions that were somewhat inconsistent with one another. In other words, I wanted to play with the interventions outlined in Categories 3 and 4 of our design ideas, as described in the previous section: thematic framing that is at odds with in-game realities, and opportunities for collective action. How, we asked, would players negotiate these ambiguous conditions? (Incidentally, we would not be testing the original question for which Brent had created Eden, which was to consider how visual theming and food availability would impact gameplay.)

Eden was set to Survival mode, so that players could fight each other; they would have to find food and defend themselves from environmental hazards (just as in Adventure mode), but would also be able to mine, craft, and build. We hinted to our players that the new map would have environmental hazards, and that although it would still be competitive like the previous game, they did not necessarily have to slaughter each other right away. The chief danger was from monsters, which could survive even during daylight under the deep shade of Eden’s giant trees. With less incentive to kill each other, and more incentive to work together for mutual shelter and defence, players largely ignored the “Hunger Games” aspect and played what looked more like a typical collaborative Minecraft survival game. The players had little incentive to kill each other, and many other more interesting things that they could do instead. Either everyone was biding their time, waiting for their moment to wipe out all the other players, or the competition component of the game became an afterthought, something to be permanently deferred. When we did observe violence, it was usually because someone decided to “make things more interesting” by going on a killing spree, slaughtering other players and breaking buildings until someone else managed to stop them. The majority of deaths were due to starvation and monsters.

Because of the way we ambiguously conditioned our testers’ motivations, and because many of them were not experienced Minecraft players, our playtest looked very different from Brent’s prior Eden playthrough. The intended ambiguity was accomplished through a combination of explicit, procedurally-enforced “hard” rules and implicit directives. In the former case, the use of Survival mode in contrast to Adventure modes already directs players towards collaborative and constructive modes of play, because in Adventure mode there was basically nothing else to do but fight to the death. This change alone might have been enough to alter player behaviour, but I was concerned that if I did not provide any additional hints (the aforementioned “implicit directives”), players would repeat the same pattern of violence from the prior game without pausing to consider how the new map could be approached differently—which would not be a very interesting finding.

In hindsight, I believe this was a mistake. It would have been much more significant to see if Adventure versus Survival alone made a difference. Even if players started by slaughtering each other as before, over time they would probably start to notice on their own that the affordances of this map were significantly different from the previous one—especially as they freely respawned into the world, rather than ending up trapped in a post-death jail or Spectator mode. Instead, I told the testers outright that they would be able to dig and build, and that it might be in their best interests to team up to deal with new challenges. This seemed like a transparent manipulation that made it difficult to read into their true motivations or determine what variables effected their change in behaviour.

If I did want to generate ambiguity through implicit directives, perhaps a more effective method would have been to take a cue from the proposals of Michael (When a narrative becomes a game mode) and Marie (Place for a “real” Hunger Games server?), described in the previous section, in which they suggested introducing backstory elements to shape how players approach the game. If I presented players with a narrative scenario suggesting certain motivations or gameplay goals, the manipulation might not have been as awkward or obvious—and it would also be reproducible, and controllable as a variable.

Two technical obstacles also came up during the Eden playtest.

First, I had hoped to create a structural incentive for combat by putting weapons and rare loot in chests spread around the map. If people found shiny equipment, they would probably be motivated to use it, and killing another player would allow the killer to take whatever wealth the victim had collected. I specifically wanted to see how well a publicly-available Bukkit plugin might perform at randomly generating and distributing such loot chests. Brent had used such a plugin in his playtests. However, when we searched the Bukkit mod repository, we were unable to find that same plugin. The repository is set up in such a way that searching for a specific mod by name is quite difficult, and it is also full of listings that do not have informative names or provide adequate descriptions. Furthermore, many of the listings are for outdated or incomplete mods. Promising-looking plugins in the repository either didn’t have the features I wanted, were incompatible with our server version, or had an impractically long list of dependencies. I had assumed that Bukkit plugins could already provide most of the functionality to build a conventional Hungercraft server like those on MC-Central, but this shows that it is not a simple “plug and play” process—which helps explain why major server operators write their own mods.

The second difficulty arose from the fact that the map was stuck in Hardcore mode, such that when players died, they were booted and locked out from reconnecting. Brent had configured Eden in this way because he originally tested it as an elimination game, but it ran counter to our intentions in the current playtest. The Hardcore mode setting resides in the map file itself, rather than in the server configuration’s text file. This makes it much harder to fix: instead of making a quick change to the text file, and restarting the server process, I had to shut the whole game down for several minutes and use a specialized program called NBTExplorer to edit the binary data in the map file, and change the offending flag.

I take away two lessons from these difficulties. First, despite the rhetoric of Minecraft being a flexible, extensible, near-universal platform for gameplay, it was designed with specific affordances for specific purposes and resists attempts to bend it toward other uses (such as arena combat games). Even though a wide range of things are possible, in practice some of those things are much harder than others. Second, it is far better to over-prepare than under-prepare for a playtest. We made the amateur mistake of assuming nothing would go wrong, and instead several things went wrong at once. If our team had conducted a dry run of the playtest amongst ourselves the previous week, we would have avoided these technical pitfalls. Although those pitfalls were revealing in their own way, it is difficult to observe player behaviour in detail when one is caught up trying to troubleshoot all the time.

The findings from the first exploratory phase of this project, while they provide some useful preliminary insights, are not as robust as we would like. Furthermore, our subsequent prototypes, while informed by or prior findings, were not ready when it came time for the playtest, and our design ideas suffered from a lack of clear goals and direction.

In this section, I consider several reasons why our project fell short of its ambitions, and how it might have been executed differently.

- Management experience

- I was responsible for directing a team of nine undergraduate students. However, I have little prior experience managing teams of this size and delegating tasks. As a leader, my strengths lay in my ability to find or develop tools for mutual collaboration—for instance, I found a novel way to use Trello, an online tool for delegating tasks among collaborators, as a convenient way to keep a collective record of our open coding. (It may have been more productive to separate the research/coding and the assigned tasks into two separate Trello boards, instead of using the same one for both.)

- The weakest link in my leadership was the delegation of tasks. In particular, I failed to offer clear goals and hard milestones, and I had difficulty gauging the required labour for each task. A table of deliverables, including a rapid prototyping schedule and design revision cycle for the second phase of the project, should have been established from the outset.

- Weeknotes: I do not think it means what you think it means

- Each member of the team was to produce a weekly blog post, briefly describing what they had spent the last week working on, and summarizing any challenges they encountered or any new ideas they had come up with. This record would serve both to keep us on task, and as a repository of material and ideas that could be drawn upon for later writing. It would also provide an opportunity to reflect on practice and consider if the working methods are effectively serving the needs of the project.

- Without much prior experience with this format, it appears that as a group, taking our cues from each other, we collectively implemented the “wrong” weeknote concept. Instead of weekly, brief accounts of our ongoing practice, we produced longer, bi-weekly articles on specific themes we had identified, often conducting in-depth analysis and bringing in outside research and theory. This exercise was productive, as this report demonstrates, but in the process we missed out on the self-management aspect of writing weeknotes. Furthermore, to some extent we started to see the blog posts themselves as our end products, thus gearing each week’s research towards the production of a single article, rather than towards building what we originally set out to build: a single, robust analytical framework of variable Minecraft Hunger Games design and play practices. Contributions to our Trello-based coding scheme became increasingly sparse even as the depth and quality of our blog articles ramped up.

- Labour hours and student availability

- Undergraduate students took part in this project on a voluntary basis, and while about half the team was quite committed throughout, the other half either lost interest or had to make the project take a back seat to other academic or life priorities—especially for those with regular employment, or who were in the final year of their degrees. We were not able to offer a strong retention incentive: a small honorarium of a couple hundred dollars, plus the hope of co-publishing an academic paper. These payoffs did not motivate everybody to the same extent.

- On multiple occasions, students asked me how much time they should be devoting to the project, or expressed concern that they would be unable to complete their tasks for a certain week due to other commitments. Considering a $300 payoff at the end of twelve weeks, I determined that I could not reasonably demand more than 2.5 to 3 hours of work from each student per week—roughly a quarter of the labour time that goes into student work in typical university course. Although this amounts to a significant number of collective hours across the entire team, each individual’s commitment is limited. Writing a good-quality 1000-word blog post alone could take up most of the time that a student is willing/able to commit to the project in a week, leaving little time for other research or design tasks.

- Two possible solutions exist. One would be to use a smaller team. The larger team may have been an asset early on, since it allowed us to gather a lot of data from many different Hunger Games servers. Our design brainstorming also produced a wide variety of ideas to choose from. However, when the time came to narrow in on preparing a single prototype for playtesting, the larger team became a liability. Most prototype ideas never made it beyond a “half-baked” state because working individually, the students did not have enough time to develop them further. It may have been better to allocate a larger number of hours to a smaller number of people. This might have given participants enough time to start and finish multiple tasks each week. Another possibility would be to make the project part of an independent or directed study course for university credit: then participants could be expected to work 8 to 12 hours on the project every week, and this commitment would be part of their normal courseload, rather than an addition to it.

- Lack of a rapid prototyping environment

- Although we had intended for our playtesting prototype to be a group effort, the map we ended up using was independently developed by Brent, since it was in the most complete state when it came time for playtesting.

- Although our thin, lackluster design cycle is due in large part to the team size and time commitment issues discussed above, we also lacked a technological framework to facilitate collaboration. Here, again, the affordances of Minecraft as a design platform are part of the problem, though some responsibility rests also with the university IT department’s inability to commit adequate resources and support for our research.

- Team members had two choices when designing prototypes: online or offline. Online has the advantage that two different people could build on the same Minecraft map at the same time. Saeed and Marie used the TAG research centre’s persistent Minecraft server, building their proof-of-concept in a remote area, using Creative mode. This mode of collaborative construction had worked well in the past for projects like Big Fried Chicken, but those efforts were specifically intended to experiment with constructing within the prescribed bounds of Minecraft gameplay. We had no intention of maintaining such constraints on our design practice, since most of the HG arena designers out there were almost certainly not limiting themselves to in-game Creative mode building.

- The offline mode of map design is more powerful. Instead of building in a persistent, server-hosted world, one keeps the map files on one’s local machine. This allows the use of powerful third-party editors like MCEdit, which can be used to copy-paste structures and trees and quickly create massive objects, and even has some options for procedurally generating terrain features. It also allows the designer to easily relocate the world’s spawnpoint, and permits the insertion of monster spawners (something that cannot be achieved at all in-game). The NBTExplorer program further makes it possible to add custom enchanted items, change command blocks with relative ease, and add custom monsters with special properties. Finally, with offline building, it is easy to maintain several different prototypes, or different versions of the same prototype. Any damage to the map due to testing (explosion craters, one-use-only mechanisms) can be easily reset by restoring a backup copy of the map. None of these possibilities are available in online design. However, if working offline, collaborators need to be physically collocated, and only one of them can be actively editing the map at a time.

- A highly effective rapid prototyping environment would have consisted of a machine (or cluster of machines) capable of running at least two Minecraft server instances at once, with multiple available network ports, a remotely-accessible desktop environment capable of running MCEdit, and easy file transfer access available to all participants, so that they could readily switch between offline and online work. Ideally, prototyping should not be carried out on a multiple-use shared space such as the TAG Minecraft server, so that designers can experiment with mods, revert map changes, and switch out different versions without having to worry about disrupting other users.

- A grounded-theory approach for initial exploratory investigations

- In the exploratory phase of the project, we organized the knowledge we were collecting about Hungercraft using a rough facsimile of Corbin and Strauss’s (1990) “open coding” process, inducing the salient categories of analysis from field observations themselves rather than working from a pre-determined framework.

- The project would have benefited from a stronger adherence to the methods of grounded theory. Although developing grand explanatory theories of Minecraft Hunger Games was not our goal, much might have been gained by carrying out systematic qualitative data collection, producing detailed written field notes, and carrying analysis of those field notes through the first two phases of the method—open coding and axial coding (Corbin and Strauss, 1990, pp. 12-13). Without written fieldnotes, much data we might have retained is now lost. Furthermore, as the process of writing field notes encourages the researcher to cast a wide net and treat everything as data, we might not have fallen so readily into the trap of selecting our collection and analysis tasks with only the next week’s blog post in mind. The “concepts” that emerge from axial coding would map onto variables that we would experiment with in our designs. (Naturally, we part ways with grounded theory as soon as we start designing our own experimental apparatus.)

Following the playtest, Brent and Tom collaborated to produce a new prototype, called “Icarus”, which combined elements of Tom’s bow-fighting design and Brent’s Eden forest. The central “citadel”, an echo of Tom’s earlier prototype, is well-lit and relatively safe (no monsters), but also lacks food resources and hiding places. Long bridges connect the citadel to the outer ring, which is hilly and covered by massive trees, creating huge pockets of darkness in which monsters can spawn. The outer ring, however, also provides necessary wood and food resources and tillable land for farming, and plenty of places to hide from other players.

The layout of Icarus also presents an effective solution to the problem, described in Section V, of collaborating on offline map design (i.e. without a shared server, but with offline tools like MCEdit available). Tom built the citadel, while Brent built the ring in a separate world; afterwards, they used MCEdit to combine the two. The layout of Icarus thus traces not only the game design goals of its creators, but also their workflow and negotiation of Minecraft’s map-building affordances.

The designers recommend that Icarus be played with about 16 people, each with two or three lives. The map is intended to make it difficult to survive as a lone wolf, encouraging players to band together into (temporary) teams that compete for scarce resources. From their description:

Because of both resource scarcity and defense based architecture, the map is prone to cause players to team up against both the environment and other players. Conflict then becomes focused on sieges and raids as opposed to pure PvP.

Originally, Icarus was also to have included a secret collective action problem: players could collaborate to build their way to a “sun” hanging high in the sky. If they reached it, they would trigger a hidden pacifist win: in doing so, tributes would reject and subvert the (apparent) procedural rhetoric of the arena, much as the characters do in the books and films. Due to its complexity, this feature was scrapped for the final version.

The Icarus map is available for download on the project website.

Icarus – the citadel and the

ring. Screenshot by Brent Calvelage.

Icarus – the citadel and the

ring. Screenshot by Brent Calvelage.

Our critiques of Minecraft Hunger Games, and our subsequent design experiments, seem as multiple dramas competing for attention on a single theatre stage. The difference between HG game designs may be understood in terms of what dramatic frames are activated—what aspects of the narrative or interaction we choose to make dramatic. Adapting Goffman’s (1959) model of frames that surround social performances, I think of these dramatic frames as the means by which participants are cast into dramatic roles as players, designers, tributes, gamemakers, builders, fighters, oppressed citizens, etc. These might be read as “emphasis frames”, in that they function by emphasizing certain elements of the interaction over others, though their primary purpose is not so much to persuade as it is to provide a framework by which players interpret their own motivations. Kaufman, Flanagan, and Punjasthitkul (2016) have noted the effect that emphasis frames can have on player motivation, though their study considers quantitative differences in levels of player engagement based on a conditioning frame, whereas I am concerned with how different framings can activate qualitatively different player behaviours. Importantly, these frames are activated not just through paratextual discourse, but through game mechanics themselves.

Below, I identify six dramatic frames that were mobilized either in the existing HG instances we researched, or in our design ideas.

- The class struggle / fight against oppression

- While a large portion of the Hunger Games film and book narratives takes place within the arena, this battle-to-the-death is hardly the main point of the story. Rather, it serves as an inflection point for the broader narrative about a fascist society in which a depraved upper class makes entertainment out of the plight of the oppressed. For the tribute, there is no escaping the sense of injustice at having been thrust unwillingly into this bloody spectacle, nor can the promise of a better life for the victor be forgotten. The protagonists at first simply struggle to survive within this system, and later fight to change it.

- From our observations, this frame was never mobilized in Minecraft Hunger Games, which tend to focus exclusively on dramatizing the deathmatch itself (see below). In fact, these narrative underpinnings are actively erased. Hungercraft has none of the darkness associated with the source narrative—it really is all just in good fun.

- Section V of this report, in particular the proposals of Michael and Marie, has described how we might usefully activate the broader Hunger Games story as “background” to a Minecraft minigame to provide players with a more complex set of motivations and incentives.

- The combat deathmatch

- This is what the “well oiled machine” Hungercraft servers focus on, to the exclusion of all else. Everything is set up to provide fast-paced play with direct, violent confrontation between players. Death is usually due to combat, rather than environmental hazards or starvation—though food is still important for restoring hit points. Variable tactics are limited to whether you chase/attack or run, and whether you take risks to seek out chests with loot.

- The conflict of nature

- PvE elements, a major part of the HG source narrative, are only present in some Minecraft HG scenarios, such as that described by Meghan in A case for teamwork). PvE is dramatized in Brent’s Eden/Hell test, in which the relative hostility of the environment is predicted to have an impact on player behaviour.

- Variable tactics, interpersonal drama, and deadly intrigue

- Team members remarked more often on the absence, rather than the presence, of this dramatic frame in Hungercraft. Brent’s Spoilsports, cheats, and undesirables shows that there is little support for dramatizing “alternative” strategies like running and hiding, while Gersande’s Crafting autonomy points to how Hungercraft typically misses the dramatic intrigue—the game of trust, bluff, and betrayal—that arises when “one’s allies are also explicitly one’s adversaries.” The Icarus design makes a point of attempting to leverage this drama.

- Building and crafting: Minecraft as Lego

- Relevant dramatic frames are not drawn only from the Hunger Games source narrative: Hungercraft scenarios are also variable in which of Minecraft’s affordances they mobilize, and which they suppress. Minecraft is often celebrated for the creative bricolage it enables, prompting favourable comparisons to Lego (Duncan, 2011, p. 6). As cited in Section VI, playtester Alex Kozina critiqued MC-Central’s Hungercraft for its lack of building and crafting affordances, while praising Eden for having these features enabled. Although the choice of Adventure versus Survival mode plays a major role in determining whether creative construction will be foregrounded, it is also necessary that the arena provide the right diversity of raw materials—for instance, Eden had a geographic depth that enabled crafting and building activities, whereas Hell did not, despite both being played in Survival mode.

- The spectacle of game design

- At some point, our design efforts began to dramatize the process of game design itself, as a sort of metagame. For instance, although each of Hell and Eden focuses on features of the arena environment in some way, when taken together, their contrast serves to make a compelling question out of the design experiment itself. Instead of asking, “Who will win?” we ask, “How will the environment affect gameplay?” The playtesters are not insulated from this metanarrative either, since in playing both maps they become conscious of the designer’s motives. Thus, each playtester pays attention to their own performance as a competitor but also keeps a critical eye towards their own behaviours and the design of the surrounding arena.

- A similar focus on trying to extract compelling “findings” from our final playtest may have been behind my clumsy efforts to create ambiguous incentives for our playtesters.

Any attempt to craft new gameplay experiences in Hungercraft or any other Minecraft minigame genre should, therefore, start with the question: what aspect of this experience do we want to dramatize and focus on? What should the spectacle, or “main event”, be? What do we want to downplay, or push to the periphery? If, as we originally planned, we want to design Hungercraft scenarios that enable players to interrogate sociological questions (while still remaining Hungercraft), these questions are crucial to guide us towards a product that intentionally and clearly—rather than accidentally or clumsily—foregrounds and dramatizes the topics we want to explore.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative sociology 13(1), 3-21.

Duncan, S. C. (2011). Minecraft, beyond construction and survival. Well Played: a journal on video games, value and meaning 1(1), 1-22. Retrieved from http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2207097

Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York, NY: Anchor.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Kaufman, G., Flanagan, M., & Punjasthitkul, S. (2016). Investigating the impact of ‘emphasis frames’ and social loafing on player motivation and performance in a crowdsourcing game. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 4122-4128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858588

Star, S., & Griesemer, J. (1989). Institutional ecology, 'translations' and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley's Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Social Studies of Science 19(3), 387–420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

Strauss, A. (1987). Qualitative analysis. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Copyright © 2017, Nic Watson and Milieux Center for Arts, Culture, and Technology

Last updated: 2017-06-30